Is your phone draining its battery too quickly? The problem may depend on the different protocols we use to surf the web, and the latest ones are not necessarily the most energy-efficient. This is the conclusion of a study conducted by the University of Pisa and the CNR Institute for Informatics and Telematics, recently published in the journal Pervasive and Mobile Computing.

Specifically, the researchers set out to evaluate the energy consumption of smartphones and Internet of Things (IoT) devices in relation to the various HTTP protocols that underpin data transmission over the Internet.

“In general, when we talk about the different versions of the HTTP protocol, the focus is on ‘performance’, which is the time required to download data and resources over the network,” explains Alessio Vecchio, author of the study and professor at the Department of Information Engineering at the University of Pisa. “Our study, on the other hand, focused on energy consumption, which is particularly relevant in the context of the Internet of Things (IoT), where many devices are battery-powered. In this context, saving energy makes it possible to significantly extend the life of the device, avoiding the need to replace or recharge batteries, with positive consequences in terms of sustainability and usability.”

A photo of the system

The HTTP protocol is one of the most widely used communication protocols in computer networks; suffice it to say that the web is based on it. Communication between IoT devices, such as sensors or home automation systems, is also often based on the HTTP protocol. Currently, the three main versions are HTTP/1.1, HTTP/2 and the newer HTTP/3, which differ significantly in terms of performance. The study found that HTTP/3, which is generally more efficient than the previous versions, can consume up to 30% more in some scenarios. This happens, for example, when there is a lot of data to transfer, while it consumes less than the others when the volume of data is smaller.

“Our study is important for two reasons, one practical and one scientific,” Vecchio points out. ‘From a practical point of view, thanks to the results obtained, those who are interested in building systems that use smartphones and IoT devices can make choices that take into account energy aspects. From a scientific point of view, new research scenarios are opening up, such as the study of intelligent algorithms capable of dynamically selecting the most energy-efficient version of the HTTP protocol depending on the communication scheme, the amount of data to be transferred and the network conditions.”

The research was carried out in the context of the Future-Oriented REsearch LABoratory (FoReLab), a project of the Department of Information Engineering of the University of Pisa, funded by the Ministry of University and Research (MUR) within the framework of the Departments of Excellence programme.

Besides Alessio Vecchio, the study was conducted by Chiara Caiazza, PhD student in Smart Computing (joint PhD programme of the Universities of Florence, Pisa and Siena) and Valerio Luconi, PhD student in Information Engineering at the University of Pisa in 2016 and researcher at the CNR Institute of Informatics and Telematics since 2019.

All three participants in the research group share an interest and concern for environmental issues, in particular energy sustainability. Therefore, the study of the energy implications of network protocols was an excellent start to combine research aspects related to computer science and systems engineering with energy saving issues.

Il professor Forti dell’Università di Pisa nel Consiglio Direttivo dell’Istituto Nazionale di Fisica

Il professore Francesco Forti (foto), docente del Dipartimento di Fisica dell’Università di Pisa, è entrato a far parte nel Consiglio direttivo dell'Istituto Nazionale di Fisica Nucleare (INFN) come rappresentante del Ministero dell'Università e Ricerca. La nomina ufficiale è arrivata lo scorso dicembre a firma della Ministra Anna Maria Bernini. Forti, che resterà in carica per il prossimo quadriennio, si è laureato nel 1985 all’Università di Pisa come allievo della Scuola Normale Superiore. Professore ordinario dell’Ateneo pisano dal 2016, ha lavorato al CERN di Ginevra, al Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory e al laboratorio SLAC a Stanford in California. Dal 2013 partecipa all'esperimento Belle II presso il laboratorio KEK, Tsukuba in Giappone.

“Grazie anche al PNRR viviamo un momento molto dinamico in cui vengono poste le basi delle infrastrutture di ricerca per le sfide del futuro, in cui l’INFN gioca da protagonista - ha detto Forti - Avendo iniziato la mia carriera scientifica come ricercatore INFN, poter partecipare alla gestione dell’ente è per me fonte di grande soddisfazione, e spero di poter contribuire al rafforzamento della sua eccellenza scientifica.”

L'INFN è un ente pubblico nazionale che svolge attività di ricerca, teorica e sperimentale, nei campi della fisica subnucleare, nucleare e astroparticellare. Il Consiglio direttivo esercita le funzioni di indirizzo e opera le scelte di programmazione scientifica.

Il professor Forti dell’Università di Pisa nel Consiglio Direttivo dell’Istituto Nazionale di Fisica

Il professore Francesco Forti (foto), docente del Dipartimento di Fisica dell’Università di Pisa, è entrato a far parte nel Consiglio direttivo dell'Istituto Nazionale di Fisica Nucleare (INFN) come rappresentante del Ministero dell'Università e Ricerca. La nomina ufficiale è arrivata lo scorso dicembre a firma della Ministra Anna Maria Bernini. Forti, che resterà in carica per il prossimo quadriennio, si è laureato nel 1985 all’Università di Pisa come allievo della Scuola Normale Superiore. Professore ordinario dell’Ateneo pisano dal 2016, ha lavorato al CERN di Ginevra, al Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory e al laboratorio SLAC a Stanford in California. Dal 2013 partecipa all'esperimento Belle II presso il laboratorio KEK, Tsukuba in Giappone.

Il professore Francesco Forti (foto), docente del Dipartimento di Fisica dell’Università di Pisa, è entrato a far parte nel Consiglio direttivo dell'Istituto Nazionale di Fisica Nucleare (INFN) come rappresentante del Ministero dell'Università e Ricerca. La nomina ufficiale è arrivata lo scorso dicembre a firma della Ministra Anna Maria Bernini. Forti, che resterà in carica per il prossimo quadriennio, si è laureato nel 1985 all’Università di Pisa come allievo della Scuola Normale Superiore. Professore ordinario dell’Ateneo pisano dal 2016, ha lavorato al CERN di Ginevra, al Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory e al laboratorio SLAC a Stanford in California. Dal 2013 partecipa all'esperimento Belle II presso il laboratorio KEK, Tsukuba in Giappone.

“Grazie anche al PNRR viviamo un momento molto dinamico in cui vengono poste le basi delle infrastrutture di ricerca per le sfide del futuro, in cui l’INFN gioca da protagonista - ha detto Forti - Avendo iniziato la mia carriera scientifica come ricercatore INFN, poter partecipare alla gestione dell’ente è per me fonte di grande soddisfazione, e spero di poter contribuire al rafforzamento della sua eccellenza scientifica.”

L'INFN è un ente pubblico nazionale che svolge attività di ricerca, teorica e sperimentale, nei campi della fisica subnucleare, nucleare e astroparticellare. Il Consiglio direttivo esercita le funzioni di indirizzo e opera le scelte di programmazione scientifica.

Il telefonino che si scarica troppo velocemente? Il problema può dipendere dai vari protocolli con cui navighiamo in rete e non è detto che quelli più recenti siano anche i più vantaggiosi dal punto di vista energetico. La notizia arriva da uno studio dell’Università di Pisa e dell’Istituto di Informatica e Telematica del CNR recentemente pubblicato sulla rivista Pervasive and Mobile Computing.

In particolare, l’obiettivo dei ricercatori era di valutare il consumo energetico di smartphone e dispositivi di Internet of Things (IoT) rispetto ai diversi protocolli HTTP che sono alla base della trasmissione dati sul Web.

“Generalmente quando si parla delle differenti versioni del protocollo HTTP l’attenzione è focalizzata sulle “prestazioni” intese come il tempo necessario a scaricare dati e risorse mediante la rete – spiega Alessio Vecchio autore dello studio e docente al Dipartimento di Ingegneria dell'Informazione dell’Ateneo pisano – Il nostro studio invece si è concentrato sul consumo energetico che è particolarmente rilevante nel contesto dell’Internet delle Cose (Internet of Things), dove molti dispositivi sono alimentati a batteria. In questo ambito risparmiare energia consente di allungare significativamente il tempo di vita del dispositivo, evitando la sostituzione o la ricarica delle batterie con conseguenze positive in termini di sostenibilità e usabilità”.

Il protocollo HTTP è tra i protocolli di comunicazione più usati nelle reti informatiche, basti pensare che il Web si basa su di esso. Anche la comunicazione tra dispositivi IoT, quali sensori o sistemi per la domotica, è spesso basata sul protocollo HTTP. Attualmente le tre versioni principali sono HTTP/1.1, HTTP/2, e il più recente HTTP/3, che differiscono in modo sostanziale tra di loro, anche per prestazioni energetiche. Come ha rivelato lo studio, in alcuni scenari HTTP/3, che generalmente è più efficiente delle altre versioni, può consumare fino al 30% in più. Questo, per esempio, accade quando i dati da trasferire sono molti, mentre consuma meno degli altri quando i dati sono pochi.

“Il nostro studio è importante per due motivi, uno di carattere pratico e uno di carattere scientifico – sottolinea Vecchio - Dal punto di vista pratico, grazie ai risultati ottenuti, è possibile, per chi sia interessato a costruire sistemi che facciano uso di smartphone e dispositivi IoT, fare delle scelte che tengano conto degli aspetti di natura energetica. Dal punto di vista scientifico, si aprono nuovi scenari di ricerca. Ad esempio, lo studio di algoritmi intelligenti che siano

La ricerca è stata svolta nel contesto di Future-Oriented REsearch LABoratory (FoReLab), un progetto del Dipartimento di Ingegneria dell’Informazione dell’Università di Pisa finanziato dal Ministero dell’Università e della Ricerca (MUR) con il programma Dipartimenti di Eccellenza.

Hanno partecipato allo studio insieme ad Alessio Vecchio, Chiara Caiazza, Dottore di Ricerca in Smart Computing (programma di dottorato congiunto erogato dalle Università di Firenze, Pisa e Siena) e Valerio Luconi, Dottore di Ricerca in Ingegneria dell’Informazione presso Università di Pisa nel 2016 e ricercatore presso Istituto di Informatica e Telematica del CNR dal 2019.

Tutti e tre i partecipanti al gruppo di ricerca sono accomunati dall’interesse e dall’attenzione per le tematiche ambientali, in particolare per la sostenibilità energetica. Lo studio delle implicazioni energetiche dei protocolli di rete è quindi stato un ottimo punto di incontro per coniugare aspetti di ricerca legati all’informatica e all’ingegneria dei sistemi con tematiche di risparmio energetico.

Il telefonino che si scarica troppo velocemente? Il problema può dipendere dai vari protocolli con cui navighiamo in rete e non è detto che quelli più recenti siano anche i più vantaggiosi dal punto di vista energetico. La notizia arriva da uno studio dell’Università di Pisa e dell’Istituto di Informatica e Telematica del CNR recentemente pubblicato sulla rivista Pervasive and Mobile Computing.

In particolare, l’obiettivo dei ricercatori era di valutare il consumo energetico di smartphone e dispositivi di Internet of Things (IoT) rispetto ai diversi protocolli HTTP che sono alla base della trasmissione dati sul Web.

“Generalmente quando si parla delle differenti versioni del protocollo HTTP l’attenzione è focalizzata sulle “prestazioni” intese come il tempo necessario a scaricare dati e risorse mediante la rete – spiega Alessio Vecchio autore dello studio e docente al Dipartimento di Ingegneria dell'Informazione dell’Ateneo pisano – Il nostro studio invece si è concentrato sul consumo energetico che è particolarmente rilevante nel contesto dell’Internet delle Cose (Internet of Things), dove molti dispositivi sono alimentati a batteria. In questo ambito risparmiare energia consente di allungare significativamente il tempo di vita del dispositivo, evitando la sostituzione o la ricarica delle batterie con conseguenze positive in termini di sostenibilità e usabilità”.

Il protocollo HTTP è tra i protocolli di comunicazione più usati nelle reti informatiche, basti pensare che il Web si basa su di esso. Anche la comunicazione tra dispositivi IoT, quali sensori o sistemi per la domotica, è spesso basata sul protocollo HTTP. Attualmente le tre versioni principali sono HTTP/1.1, HTTP/2, e il più recente HTTP/3, che differiscono in modo sostanziale tra di loro, anche per prestazioni energetiche. Come ha rivelato lo studio, in alcuni scenari HTTP/3, che generalmente è più efficiente delle altre versioni, può consumare fino al 30% in più. Questo, per esempio, accade quando i dati da trasferire sono molti, mentre consuma meno degli altri quando i dati sono pochi.

“Il nostro studio è importante per due motivi, uno di carattere pratico e uno di carattere scientifico – sottolinea Vecchio - Dal punto di vista pratico, grazie ai risultati ottenuti, è possibile, per chi sia interessato a costruire sistemi che facciano uso di smartphone e dispositivi IoT, fare delle scelte che tengano conto degli aspetti di natura energetica. Dal punto di vista scientifico, si aprono nuovi scenari di ricerca. Ad esempio, lo studio di algoritmi intelligenti che siano in grado di scegliere dinamicamente la versione del protocollo HTTP più efficiente dal punto di vista energetico a seconda dello schema di comunicazione, della quantità di dati da trasferire e delle condizioni della rete”.

Una foto del sistema di monitoraggio

La ricerca è stata svolta nel contesto di Future-Oriented REsearch LABoratory (FoReLab), un progetto del Dipartimento di Ingegneria dell’Informazione dell’Università di Pisa finanziato dal Ministero dell’Università e della Ricerca (MUR) con il programma Dipartimenti di Eccellenza.

Hanno partecipato allo studio insieme ad Alessio Vecchio, Chiara Caiazza, Dottore di Ricerca in Smart Computing (programma di dottorato congiunto erogato dalle Università di Firenze, Pisa e Siena) e Valerio Luconi, Dottore di Ricerca in Ingegneria dell’Informazione presso Università di Pisa nel 2016 e ricercatore presso Istituto di Informatica e Telematica del CNR dal 2019.

Tutti e tre i partecipanti al gruppo di ricerca sono accomunati dall’interesse e dall’attenzione per le tematiche ambientali, in particolare per la sostenibilità energetica. Lo studio delle implicazioni energetiche dei protocolli di rete è quindi stato un ottimo punto di incontro per coniugare aspetti di ricerca legati all’informatica e all’ingegneria dei sistemi con tematiche di risparmio energetico.

Correggere in tempo reale le cattive posture che si assumono a lavoro, via smartwatch, il tutto nel pieno rispetto di privacy e riservatezza. È questo l’obiettivo di un innovativo sistema basato sull’intelligenza artificiale ideato e sperimentato dall’Università di Pisa. I risultati della ricerca, coordinata da Francesco Pistolesi, ricercatore presso il Dipartimento di Ingegneria dell'Informazione, sono stati pubblicati sulla rivista Computers in Industry.

“L'affaticamento e la ripetitività di svariate mansioni lavorative portano spesso gli operatori ad assumere posture incongrue perché magari sono momentaneamente percepite come comode — spiega Pistolesi — questo però, a medio e lungo termine, provoca uno stress dell’apparato muscolo-scheletrico; le statistiche ci dicono che, in tutto il mondo, oltre un lavoratore su quattro soffre di mal di schiena, con conseguenti sofferenze e perdita di oltre 264 milioni di giorni lavorativi ogni anno”.

Il dispositivo dell’Ateneo pisano (si veda Figura 1) è stato testato coinvolgendo operatori durante l'esecuzione di varie mansioni standardizzate (avvitatura, saldatura e assemblaggio). Il sistema è costituito da un'unità basata su intelligenza artificiale che riceve continuativamente dati da uno smartwatch e un sensore LiDAR — una tecnologia avanzata che usa impulsi laser per misurare distanze e creare mappe dell'ambiente. Durante i test, il sistema ha monitorato le posizioni di braccio, spalla, tronco e gambe, acquisendo dati che non sono in grado di rivelare informazioni sensibili del lavoratore.

L’intelligenza artificiale ha identificato le posture con una precisione media superiore al 98%, rilevando inoltre gli scostamenti dalle posizioni degli arti raccomandate dallo standard UNI ISO 11226 (Ergonomics — Evaluation of static working postures). Questo standard fornisce raccomandazioni per la valutazione del rischio per la salute della popolazione adulta attiva, derivate da studi sperimentali sul carico muscoloscheletrico, sul disagio/dolore e sulla resistenza/fatica associati alle posture di lavoro.

“Il nuovo paradigma dell’Industria 5.0 usa l'intelligenza artificiale (AI) mettendo al centro l’essere umano — sottolinea Pistolesi — la tecnologia non ci sostituisce, ma ci aiuta. Si tratta in altre parole di pensare a dispositivi, come quello che abbiamo ideato, che mettano in primo piano il benessere e diritti di lavoratrici e lavoratori, in particolare la privacy, che le tecnologie basate sull'analisi video possono mettere a rischio. Si pensi per esempio ad attacchi informatici che si impadroniscono di immagini di parti del corpo sensibili dei lavoratori, usate per rilevare la postura. I dati registrati dal nostro sistema, invece, anche se trafugati, non possono ricondurre ad alcuna informazione che violi la riservatezza dei dipendenti di un'azienda. Ciò fa sì che i lavoratori si sentano più tutelati e considerati, aumentando sia il benessere che la produttività. Ecco perché negli anni a venire sarà sempre più importante progettare sistemi ispirati all'intelligenza artificiale orientata all'essere umano, la cosiddetta human-centered AI”.

Assieme a Francesco Pistolesi, hanno collaborato alla ricerca Michele Baldassini, assegnista di ricerca presso il Dipartimento di Ingegneria dell'Informazione, e Beatrice Lazzerini, professoressa ordinaria presso lo stesso dipartimento per oltre vent'anni, e attualmente titolare di un contratto di ricerca a titolo gratuito.

Correggere in tempo reale le cattive posture che si assumono a lavoro, via smartwatch, il tutto nel pieno rispetto di privacy e riservatezza. È questo l’obiettivo di un innovativo sistema basato sull’intelligenza artificiale ideato e sperimentato dall’Università di Pisa. I risultati della ricerca, coordinata da Francesco Pistolesi, ricercatore presso il Dipartimento di Ingegneria dell'Informazione, sono stati pubblicati sulla rivista Computers in Industry.

“L'affaticamento e la ripetitività di svariate mansioni lavorative portano spesso gli operatori ad assumere posture incongrue perché magari sono momentaneamente percepite come comode — spiega Pistolesi — questo però, a medio e lungo termine, provoca uno stress dell’apparato muscolo-scheletrico; le statistiche ci dicono che, in tutto il mondo, oltre un lavoratore su quattro soffre di mal di schiena, con conseguenti sofferenze e perdita di oltre 264 milioni di giorni lavorativi ogni anno”.

Il team di ricerca da sinistra Michele Baldassini, Francesco Pistolesi e Beatrice Lazzerini

Il dispositivo dell’Ateneo pisano (si veda Figura 1) è stato testato coinvolgendo operatori durante l'esecuzione di varie mansioni standardizzate (avvitatura, saldatura e assemblaggio). Il sistema è costituito da un'unità basata su intelligenza artificiale che riceve continuativamente dati da uno smartwatch e un sensore LiDAR — una tecnologia avanzata che usa impulsi laser per misurare distanze e creare mappe dell'ambiente. Durante i test, il sistema ha monitorato le posizioni di braccio, spalla, tronco e gambe, acquisendo dati che non sono in grado di rivelare informazioni sensibili del lavoratore.

L’intelligenza artificiale ha identificato le posture con una precisione media superiore al 98%, rilevando inoltre gli scostamenti dalle posizioni degli arti raccomandate dallo standard UNI ISO 11226 (Ergonomics — Evaluation of static working postures). Questo standard fornisce raccomandazioni per la valutazione del rischio per la salute della popolazione adulta attiva, derivate da studi sperimentali sul carico muscoloscheletrico, sul disagio/dolore e sulla resistenza/fatica associati alle posture di lavoro.

“Il nuovo paradigma dell’Industria 5.0 usa l'intelligenza artificiale (AI) mettendo al centro l’essere umano — sottolinea Pistolesi — la tecnologia non ci sostituisce, ma ci aiuta. Si tratta in altre parole di pensare a dispositivi, come quello che abbiamo ideato, che mettano in primo piano il benessere e diritti di lavoratrici e lavoratori, in particolare la privacy, che le tecnologie basate sull'analisi video possono mettere a rischio. Si pensi per esempio ad attacchi informatici che si impadroniscono di immagini di parti del corpo sensibili dei lavoratori, usate per rilevare la postura. I dati registrati dal nostro sistema, invece, anche se trafugati, non possono ricondurre ad alcuna informazione che violi la riservatezza dei dipendenti di un'azienda. Ciò fa sì che i lavoratori si sentano più tutelati e considerati, aumentando sia il benessere che la produttività. Ecco perché negli anni a venire sarà sempre più importante progettare sistemi ispirati all'intelligenza artificiale orientata all'essere umano, la cosiddetta human-centered AI”.

Assieme a Francesco Pistolesi, hanno collaborato alla ricerca Michele Baldassini, assegnista di ricerca presso il Dipartimento di Ingegneria dell'Informazione, e Beatrice Lazzerini, professoressa ordinaria presso lo stesso dipartimento per oltre vent'anni, e attualmente titolare di un contratto di ricerca a titolo gratuito.

Liguria, Friuli Venezia Giulia e Trentino-Alto Adige sono le regioni più ricche di flora in Italia, anche se tanta ricchezza comprende presenze record di specie aliene. Il dato arriva da uno studio pubblicato sulla rivista Plants e coordinato da Lorenzo Peruzzi, professore del Dipartimento di Biologia dell’Università di Pisa e direttore dell'Orto e Museo Botanico dell'Ateneo.

“In ambito ecologico è noto che, all'aumentare dell'area disponibile, aumenta anche il numero di specie – spiega Peruzzi – Pertanto, quando si parla di ricchezza floristica, non basta riferirsi al numero di specie presenti, ma bisogna anche tenere conto dell'ampiezza del territorio. Il fenomeno, modellizzabile con funzioni matematiche, è noto col nome di Relazione Specie-Area (acronimo SAR, Species-Area Relationship, in inglese) ed è sullo studio di questa relazione nella flora italiana che si è basata la nostra ricerca”.

Dai risultati emerge così che le regioni più ricche di flora sono Liguria, Friuli Venezia Giulia, Trentino-Alto Adige, Abruzzo e Valle d’Aosta, mentre Sardegna, Puglia, Sicilia, Emilia-Romagna e Calabria sono le più povere. Considerando solo le specie autoctone, la classifica varia leggermente: il Trentino-Alto Adige esce dai primi posti e terzo sul podio arriva l’Abruzzo, mentre resta tutto invariato in coda. Per quanto riguarda infine le specie aliene, le regioni più ricche sono Liguria, Lombardia, Friuli Venezia-Giulia, Trentino-Alto Adige e Veneto, mentre Basilicata, Valle d’Aosta, Molise, Calabria e Puglia sono le più povere.

“Abruzzo, Valle d'Aosta e Molise sono regioni di particolare interesse naturalistico poiché mostrano una ricchezza floristica autoctona superiore all'atteso e una aliena inferiore – dice Peruzzi – Lombardia, Veneto, Toscana ed Emilia-Romagna mostrano invece problemi di conservazione potenzialmente gravi a causa alle invasioni biologiche, poiché in queste regioni tali rapporti sono invertiti. In particolare, la Toscana mostra livelli di ricchezza floristica solo lievemente inferiore all’atteso. Ciò significa, semplificando, che in questa regione vi sono più o meno tante specie native quante era lecito attendersi sulla base dell’ampiezza del suo territorio, ma anche purtroppo molte più aliene dell’atteso”.

"Abbiamo costruito un dataset di 266 flore di varie estensioni, da minuscoli isolotti come Stramanari in Sardegna ai circa 302mila km2 dell’intero territorio nazionale, e poi applicato la Relazione Specie-Area per l'intera flora vascolare italiana, per le sole specie native e per le sole specie aliene – aggiunge Marco D'Antraccoli, curatore dell'Orto Botanico dell’Università di Pisa – in questo modo siamo riusciti a valutare, per ogni flora, se il numero di specie censito fosse al di sopra o al di sotto dei valori attesi per l’area del territorio in esame".

"L'utilità di questo studio va oltre il poter confrontare in modo oggettivo la ricchezza floristica delle varie regioni italiane, ricavandone una sorta di ‘classifica’ – conclude Lorenzo Peruzzi – Infatti, per la prima volta abbiamo ricavato delle costanti specificatamente calibrate per il territorio italiano che consentiranno d'ora in poi agli studiosi di calcolare agevolmente il numero di specie di piante vascolari attese per una data area".

Oltre a Lorenzo Peruzzi e Marco D'Antraccoli, hanno collaborato alla ricerca Francesco Roma-Marzio, curatore dell’Erbario del Museo Botanico dell’Università di Pisa, Fabrizio Bartolucci e Fabio Conti dell'Università di Camerino, e Gabriele Galasso del Museo Civico di Storia Naturale di Milano.

Il Perucetus colossus è la terza scoperta scientifica più incredibile del 2023, parola di National Geographic. La prestigiosa rivista ha pubblicato pochi giorni fa la classifica delle scoperte più affascinanti realizzate nel 2023 e, tra le 11 citate, il fossile di cetaceo ritrovato in Perù dai paleontologi dell’Università di Pisa occupa il terso gradino del podio.

Ricostruzione artistica di Perucetus colossus (Alberto Gennari).

Nell’articolo del National Geographic si ricorda che “un antico cetaceo chiamato in modo appropriato Perucetus colossus potrebbe essere stato il più grande animale di sempre. Una nuova analisi di ossa fossili di questa antica balena, che solcava le acque lungo la costa del Perù più di 37 milioni di anni fa, suggerisce che l'animale potesse pesare più di 300 tonnellate e misurare 20 metri. Se fosse davvero così pesante come sospettano gli scienziati, sarebbe stato il più grande animale conosciuto mai esistito. Le balene azzurre, anche se più lunghe, intorno ai 30 metri, pesano solo circa 200 tonnellate”.

Scavo vertrebe Perucetus (Giovanni Bianucci).

La scoperta di questo eccezionale cetaceo era stata presentata in un articolo pubblicato sulle pagine di Nature a inizio agosto. I resti dello straordinario animale, un antenato delle balene e dei delfini caratterizzato da ossa grandissime e pesantissime che hanno fatto subito pensare a un mostro marino dalle proporzioni titaniche, sono riaffiorati dal Deserto di Ica, lungo la costa meridionale del Perù e sono stati studiati da un gruppo internazionale di scienziati, con in primo piano i paleontologi del Dipartimento di Scienze della Terra dell’Università di Pisa: il professor Giovanni Bianucci, primo autore e coordinatore della ricerca, il dottorando Marco Merella e il ricercatore Alberto Collareta. Allo studio hanno partecipato anche altri geologi e paleontologi italiani provenienti dalle università di Milano-Bicocca (la ricercatrice Giulia Bosio e la professoressa Elisa Malinverno) e Camerino (i professori Claudio Di Celma e Pietro Paolo Pierantoni), affiancati da ricercatori peruviani e di diverse nazionalità europee. Al cetaceo è stato dato il nome di Perucetus colossus in onore del paese sudamericano in cui è stato rinvenuto e in riferimento alla sua taglia letteralmente colossale.

Recupero vertreba Perucetus (Giovanni Bianucci).

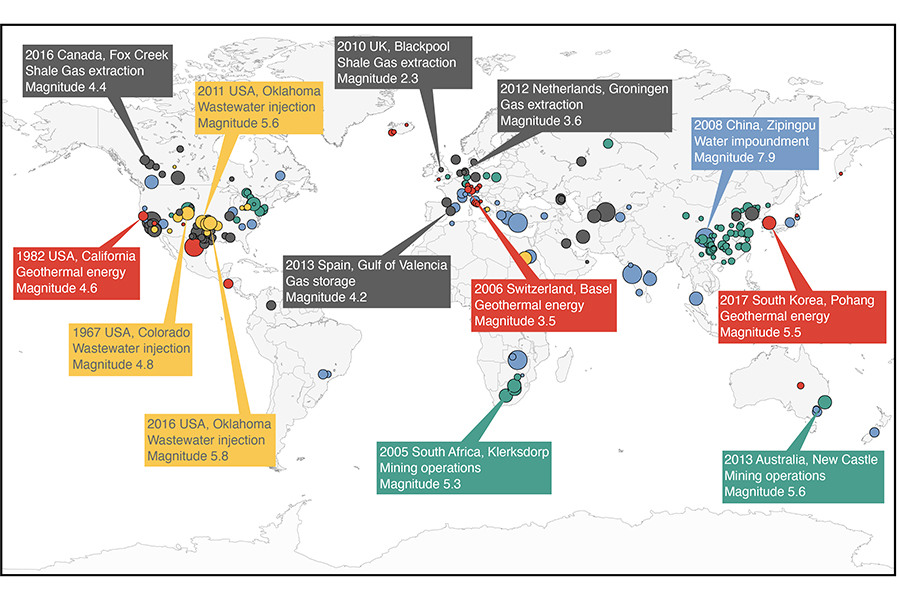

“La sismicità indotta è un tema particolare importante in questa fase di transizione energetica perché potrebbe essere uno degli ostacoli principali nello sviluppo delle attività di cattura e stoccaggio della CO2 nel sottosuolo”. E’ questo il commento di Francesco Grigoli, ricercatore del Dipartimento di Scienze della Terra dell’Università di Pisa, autore di un articolo appena pubblicato su Nature Reviews sui terremoti indotti, un fenomeno provocato direttamente o indirettamente dalle attività industriali legate allo sfruttamento del sottosuolo. Il lavoro, svolto in collaborazione con Free University Berlin, Stanford University, ETH di Zurigo e Southern University of Science and Technology cinese, fa il punto sulle più recenti ricerche in materia.

“Sebbene nella maggior parte dei casi la sismicità indotta non rappresenti un pericolo per le infrastrutture e le comunità locali, in alcuni casi si sono verificati eventi distruttivi. Uno dei casi più emblematici – spiega Grigoli - è stato il terremoto di magnitudo 5.5 avvenuto il 15 Novembre 2017 a Pohang, in Corea del Sud. Il sisma è stato causato da attività di stimolazione idraulica, una pratica vietata in Italia, per lo sfruttamento di energia geotermica”.

Come riportato su Nature Review, sebbene non ancora del tutto chiari, esistono diversi meccanismi fisici in grado di spiegare la sismicità indotta. In alcuni casi, ad esempio, la sismicità indotta è generata dall’iniezione di fluidi nel sottosuolo che, provocando un sostanziale aumento della pressione dei fluidi all’interno delle formazioni rocciose, può attivare faglie prossimali al sito industriale. In altri il fenomeno è associato alla rimozione di masse rocciose durante le attività minerarie, allo stoccaggio o all’estrazione di fluidi dal sottosuolo e al carico e scarico di bacini idraulici.

Per quanto riguarda invece la prevenzione, un aiuto arriva dal monitoraggio microsismico in tempo reale che ha un ruolo fondamentale non solo per una migliore comprensione del fenomeno, ma anche per identificare sul nascere possibili terremoti anomali di origine antropica. Un altro elemento di fondamentale importanza è poi l’implementazione di sistemi che permettano di “pronosticare” l’evoluzione della sismicità utilizzando modelli fisici, statistici o più recentemente l’intelligenza artificiale.

“La sismicità indotta è un problema complesso e intrinsecamente multidisciplinare, basato sulla combinazione di dati sismologici, geomeccanici, idrogeologici e industriali – conclude Grigoli - pertanto, non ci sono soluzioni semplici a questo problema che costituisce uno degli argomenti di ricerca principali della comunità sismologica mondiale”.