Two hundred years ago, in Pisa, Egyptology entered a university classroom for the very first time in the world. The professor was the young orientalist Ippolito Rosellini, one of the very few scholars to engage with the newly born discipline, who introduced students at the University of Pisa to the history and language of ancient Egypt. The year was 1825/26, placing Pisa six years ahead of Paris, where the first chair in Egyptology was established in 1831 under Jean-François Champollion.

“This achievement for Pisa was due in no small part to the support of Leopold II of Tuscany,” notes Gianluca Miniaci, Professor of Egyptology at the Department of Civilisations and Forms of Knowledge of the University of Pisa. “The Grand Duke’s enthusiasm also stemmed from practical considerations: in those years, Livorno was the European gateway for all Pharaonic antiquities.”

Every European court aspired to own an Egyptian collection, and Livorno soon became the main hub for this thriving trade. Ships departing from Alexandria, laden with grain and exotic goods, docked in the Tuscan port carrying statues, sarcophagi, mummies and papyri. Before long, the city’s warehouses and lazarettos were overflowing with the very artefacts that today grace the museums of Turin, Florence, Bologna, London, Paris, Berlin, Vienna and Leiden. “A genuine form of specialised tourism emerged,” notes Mattia Mancini, a member of Miniaci’s research group who has conducted studies in the State Archives of Livorno, “with antiquarians, collectors and scholars travelling to Tuscany to view these precious objects first-hand.

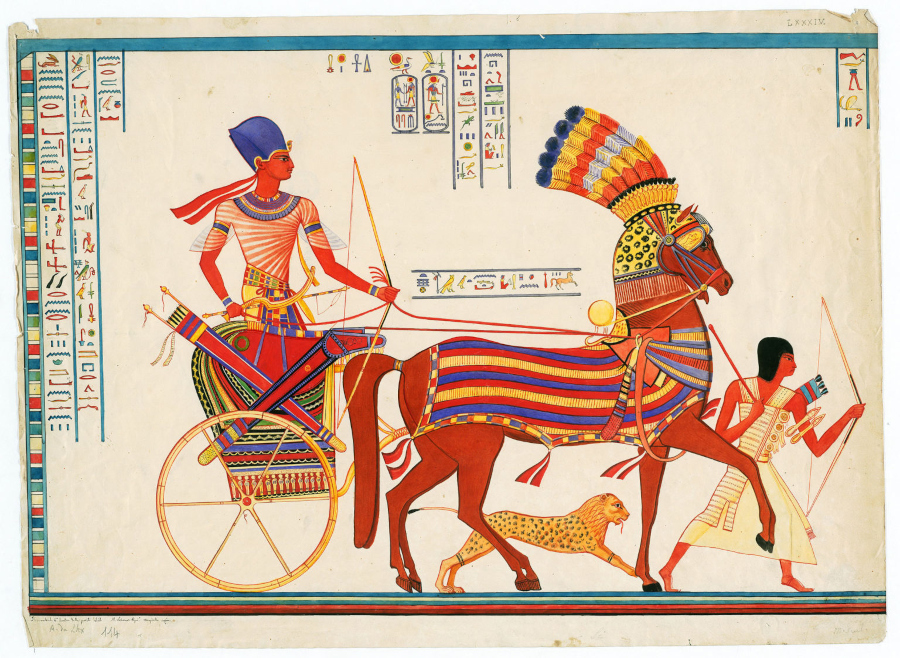

To mark the bicentenary, Egyptologists at the University of Pisa, Rosellini’s intellectual heirs, have curated a programme of events featuring lectures, an international conference in December, and an exhibition displaying pages from Rosellini’s earliest lessons together with other treasures from the University Library of Pisa, including early printed volumes, handwritten notes and the exquisite drawings created during the Franco-Tuscan expedition.

Rosellini’s engagement with Egyptology extended well beyond his teaching. Together with Champollion, he planned an extraordinary scientific journey along the Nile Valley, financed by Grand Duke Leopold II of Tuscany and King Charles X of France. The renowned Franco-Tuscan Expedition of 1828–1829 marked the very first true Egyptological mission. Accompanied by draughtsmen charged with meticulously recording the inscriptions and scenes from temples and tombs, Rosellini and Champollion laid the foundations of modern documentation. The Tuscan contingent returned to Livorno between November and December 1829 with around 2,000 artefacts destined for the Archaeological Museum of Florence, as well as an exceptional archive now preserved in the University Library of Pisa: more than 20,000 papers—including notebooks, manuscripts, letters, texts and over a thousand exquisite drawings, many in watercolour—which will be showcased in Pisa for the bicentenary.