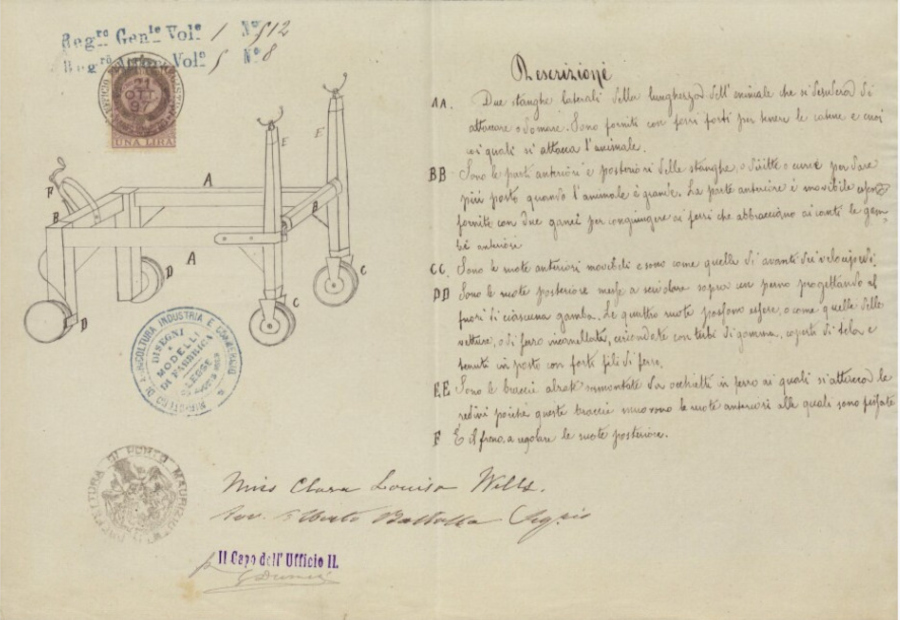

Rosa Predavalle was the first woman in Italy to obtain a patent. In 1861, she designed the Armonitone, a “muted piano” that allowed for more controlled playing. Rosa was the first woman to embody the long yet little-known history of female creativity, which has now been brought to light by the research of Marco Martinez, Professor of Economic History at the University of Pisa. This research was published in the international journal Business History.

Drawing on the study of over 330,000 patents filed in Italy between Unification and the Second World War, this research is the first to systematically record women’s inventions between 1861 and 1939. The outcome — 1,878 patents, representing 0.7% of the total — reveals that women made a significant contribution to the country’s technological development. Up until the 1920s, the growth rate of women’s patents was comparable to that of men’s. However, the Fascist regime set them back, confining women once again to the domestic sphere through propaganda and legislation.

Women’s inventions spanned mechanics, the textile industry, transport, armaments, and innovations for the home. In 1918, Francesca Giuseppa Sillani patented a military tent for the army and Lina Holzer designed a fuel economiser — a device to improve the efficiency of stoves and heating systems — in the same year. Other inventors, including Eufrasia, Marcantonia, Ersilia and Melvenia, who were active between the late 19th century and the 1930s, registered patents for industrial mechanisms and domestic devices, including spinning and sewing instruments, household tools, heating appliances, and small mechanical contraptions for everyday use.

The most active provinces were those of the industrial triangle — Milan, Turin and Genoa — along with Rome and Naples. However, manufacturing centres such as Udine, Bergamo, Pisa, Florence and Salerno also stood out for their high concentration of women’s patents, which were often connected to textile and silk processing.

Tuscany’s patent archives reveal surprising inventiveness. In Pisa, for example, Rosa Pelucchi patented a system for cocoon winding in 1869, which is evidence of the important role played by the silk sector in local production. In 1877, Carolina Cappelletto (née Pizzorni), daughter of the late Antonio, patented the so-called sugo al magro (meatless sauce) — an example of food innovation at a time when preserving food posed major technical challenges. In 1890, Giovanna Bottari obtained a patent for Soda Champagne, a carbonated drink that was registered as a medicinal preparation. Several other remarkable figures emerged in Florence and its surroundings: Francesca Cremonesi patented a roller bearing for railway vehicles — a highly technical invention that demonstrates how certain women were able to work competently in traditionally male-dominated fields such as mechanics. Adelaide Marchi devised a bingo game for the visually impaired — a project combining ingenuity and social sensitivity that anticipated the modern idea of inclusion. Lina Spinetti and Italo Spinetti registered a mourning stamp and a stamp for advertising tax on correspondence. Meanwhile, Anna Alessandrini patented a system of teaching materials for teaching arithmetic to individuals with cognitive disabilities, which is further evidence of a growing interest in special education and innovative pedagogy.

“These women were true creative entrepreneurs,” explains Marco Martinez, Professor of Economic History at the University of Pisa, ‘capable of turning ideas into technical solutions and challenging legal, cultural and social barriers.’ Our research shows how gender dynamics profoundly shaped innovation processes and how the relationship between industrialisation, culture, and rights was crucial in determining women’s opportunities. Yet the inequalities of the past still cast a shadow today: even now, in Europe, only 16% of patents are held by women.”